Koan 14: The Missing Grain

When python packaged data goes wrong

The Master asked the young cook “Where is the millet for the morning congee?”

The cook gestured to the open sack. “It is there Master where it has always been.”

The Master reached into the sack but pulled out only dust. “When the sack is tied and carried to the marketplace, the millet must travel with it. The sack itself is but a suggestion of grain.”

The cook lowered his eyes. “I forgot to check the sack.”

The Python Packaging Ecosystem

In Python projects, code is rarely enough on its own. Configuration files, database schemas, assets, and binaries often need to accompany it. These files are what allow code to function correctly in real environments.

When working directly from a source tree, all files are accessible through the filesystem. But when you build a package into a wheel or source distribution and install it elsewhere, only the files you explicitly include are carried forward. Any undeclared files vanish in the process.

The governing principle is the package manifest. If non-code files are required, you must declare them so the build system knows to include them. Without this, your project risks arriving at its destination empty-handed.

Part 1: The Initial Oversight

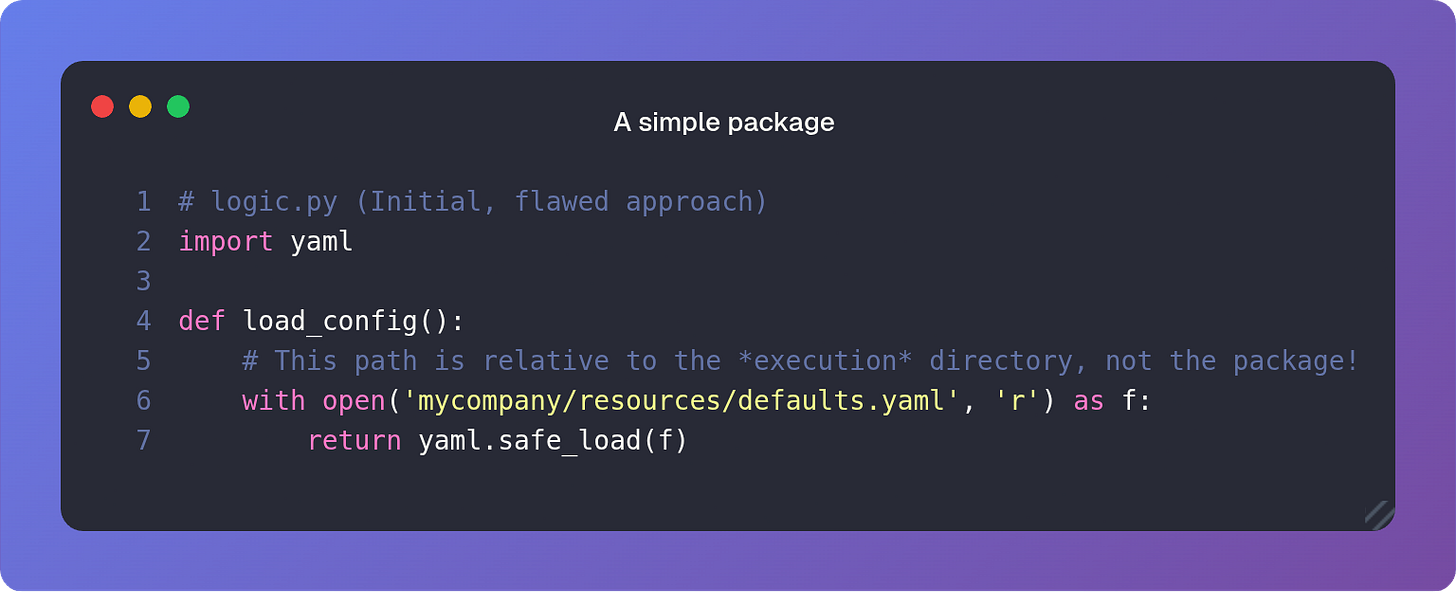

Suppose you begin with a project that reads a configuration file:

logic.py might try to access defaults.yaml:

This works only if you run the script from the project root. Change the working directory and it breaks. Reliance on the current directory is fragile.

Part 2: Editable Installs

During development, many use editable installs. Running:

pip install -e .places a reference to your source tree in site-packages. Imports resolve against the live code, so changes take effect immediately without reinstalling.

This approach removes the need to run from the project root. But when you distribute the package, if defaults.yaml was never declared as package data, users installing it elsewhere will find that Python cannot locate the file.

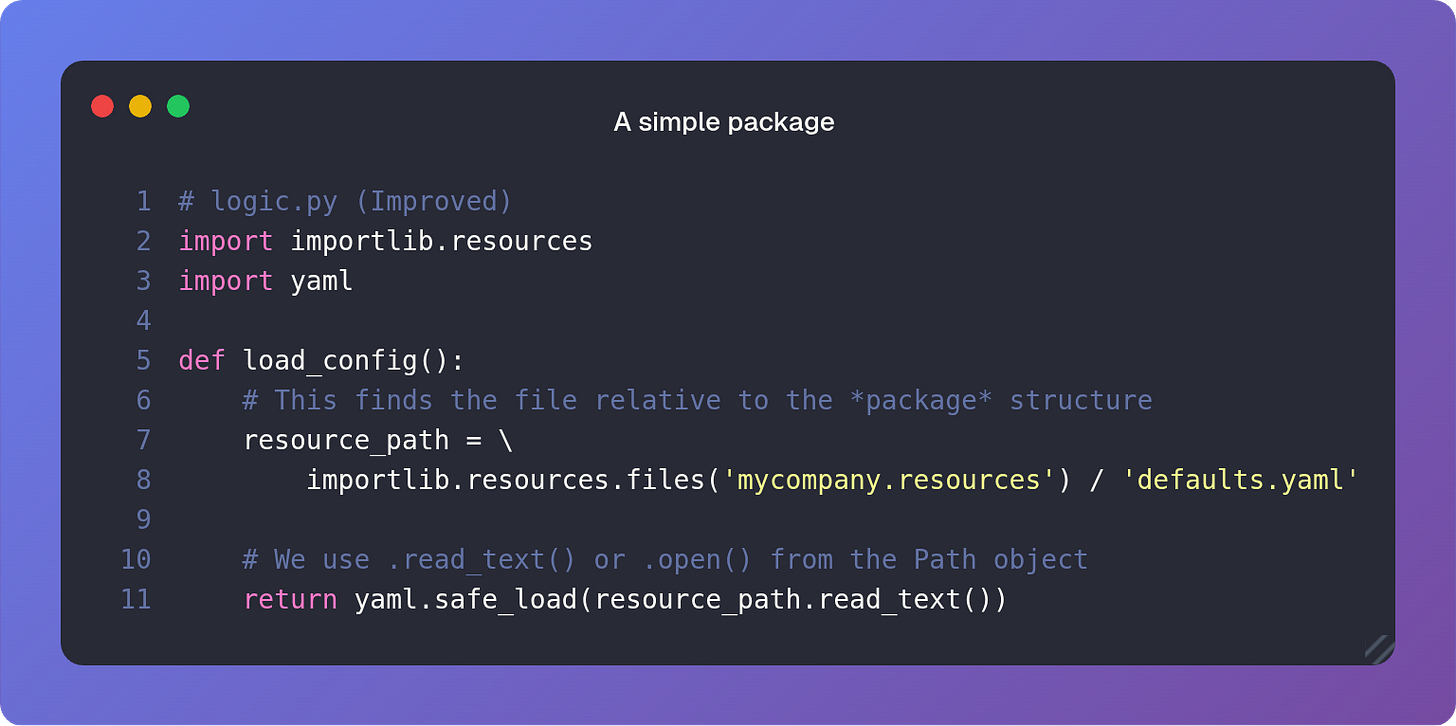

Part 3: Using importlib.resources

The recommended way to access package data is importlib.resources (or its backport for older Python versions). It looks up resources relative to the package, independent of how or where it is installed.

This resolves the path issue. But it does not solve the packaging problem: if defaults.yaml is not bundled into the distribution, it still won’t be present in the installed package.

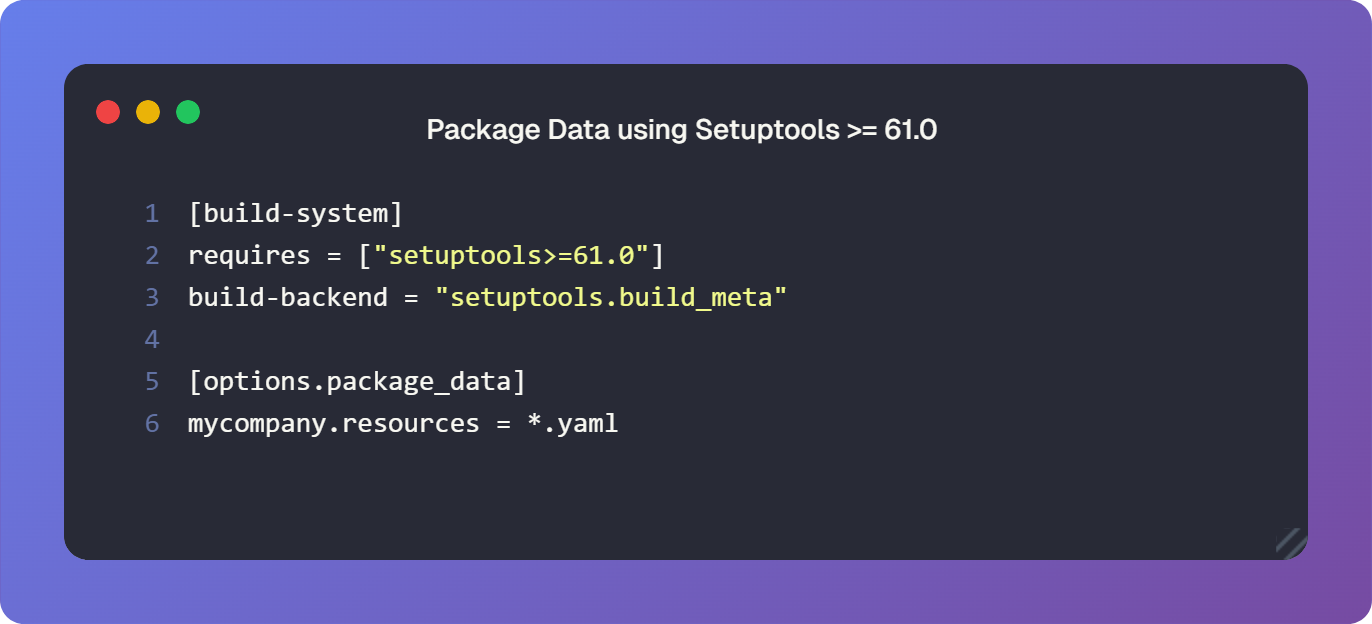

Part 4: Declaring Resources

To ensure resources travel with your package, you must declare them in your build configuration. By default, only Python source files are included.

Below are minimal pyproject.toml snippets showing how to include *.yaml files using setuptools and hatchling:

Setuptools

Hatchling

Both achieve the same effect: defaults.yaml is bundled into the wheel and available through importlib.resources.

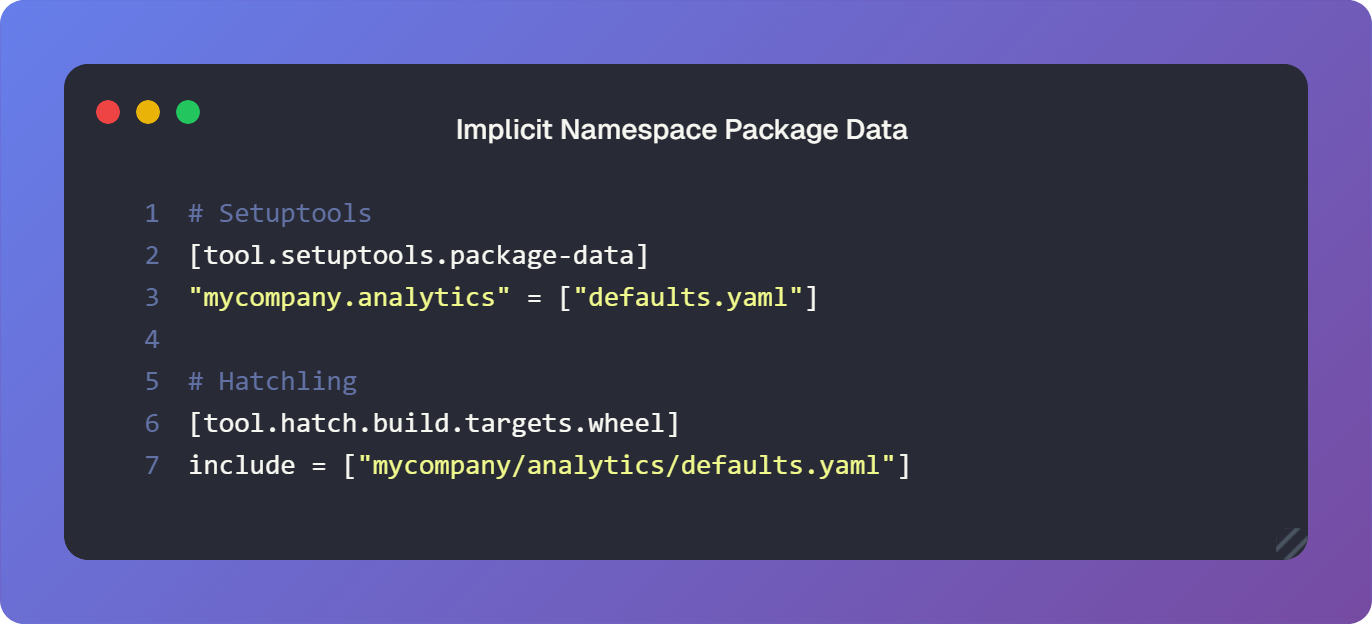

Part 5: Namespace Packages

With implicit namespace packages (PEP 420), parts of a namespace can be spread across multiple distributions. Such packages omit an __init__.py in the top-level directory, enabling a flat layout as we learnt in Koan 7:

Here, mycompany is an implicit namespace shared by two subpackages. To ensure defaults.yaml travels with mycompany.analytics, declare it under that subpackage.

This guarantees that only mycompany.analytics carries defaults.yaml, while mycompany.ml remains unaffected.

Shipping The Millet

The package manifest is the measure of completeness. If you omit declarations, your distribution will carry only dust. When crafting Python packages, verify that every essential file (code or data) travels with it.