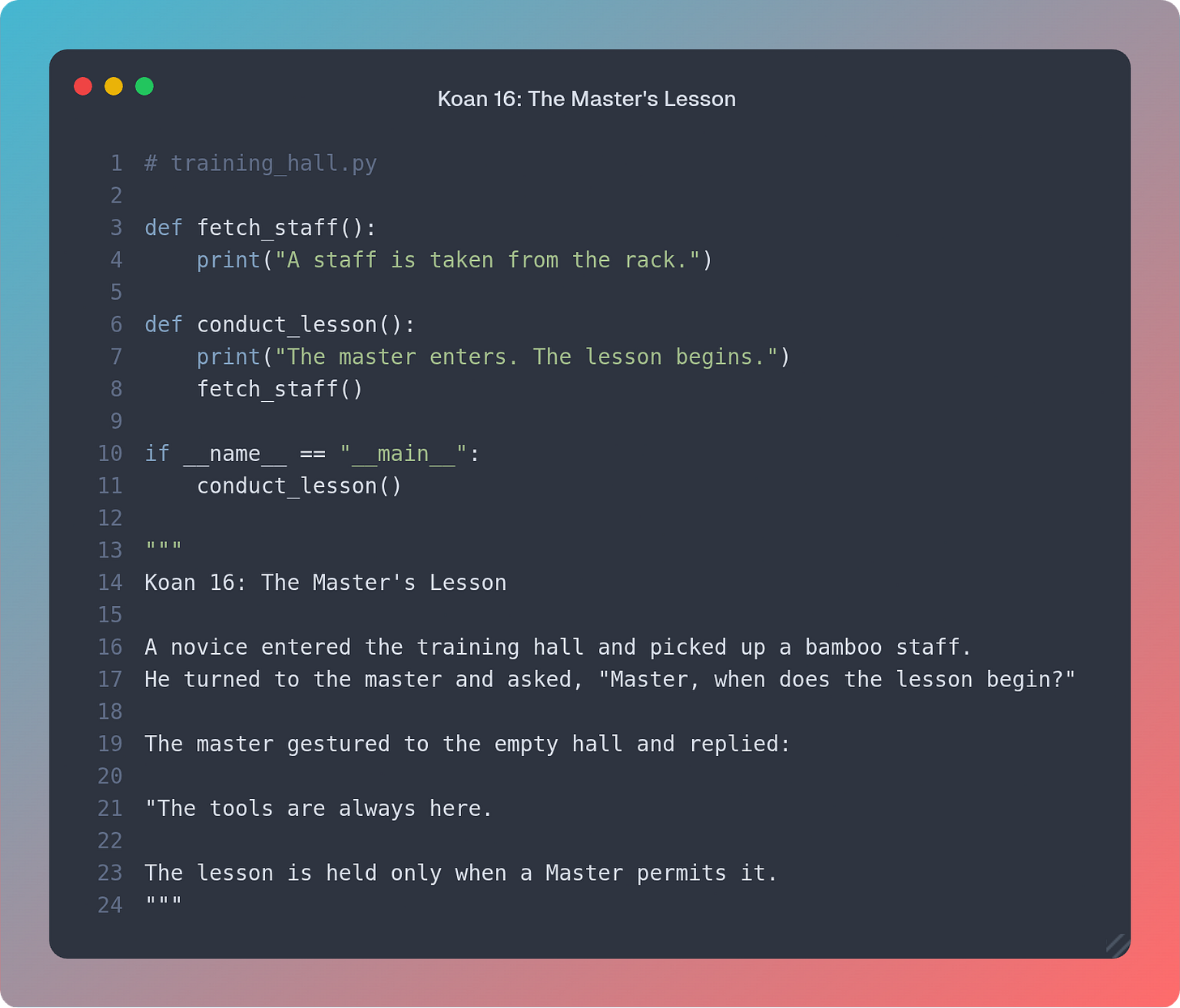

Koan 16: The Master's Lesson

Why we need "if __name__ == '__main__'"

The Hidden Teaching: The Boundary of Execution

One of the most ubiquitous pieces of Python code is the expression if __name__ == “__main__”. You will often find this in standalone scripts or entrypoints to cli tools. But why is this needed and what are the consequences if this simple statement is left out? Some of these may surprise you.

Let us begin again.

Part 1: The Dual Nature of Python Files

When Python processes a file, whether by running it directly (python training_hall.py) or by importing it (import training_hall):

It reads the code from top to bottom of the file, executing all code that is not inside a function or class definition.

It inserts all objects (functions, classes and variables) into the current namespace (using the scoping rules we learnt in Koan 4).

In our introductory snippet, the functions fetch_staff and conduct_lesson are defined on import, becoming functions available in the global scope. The code inside them is not executed. This is correct behavior for a utility.

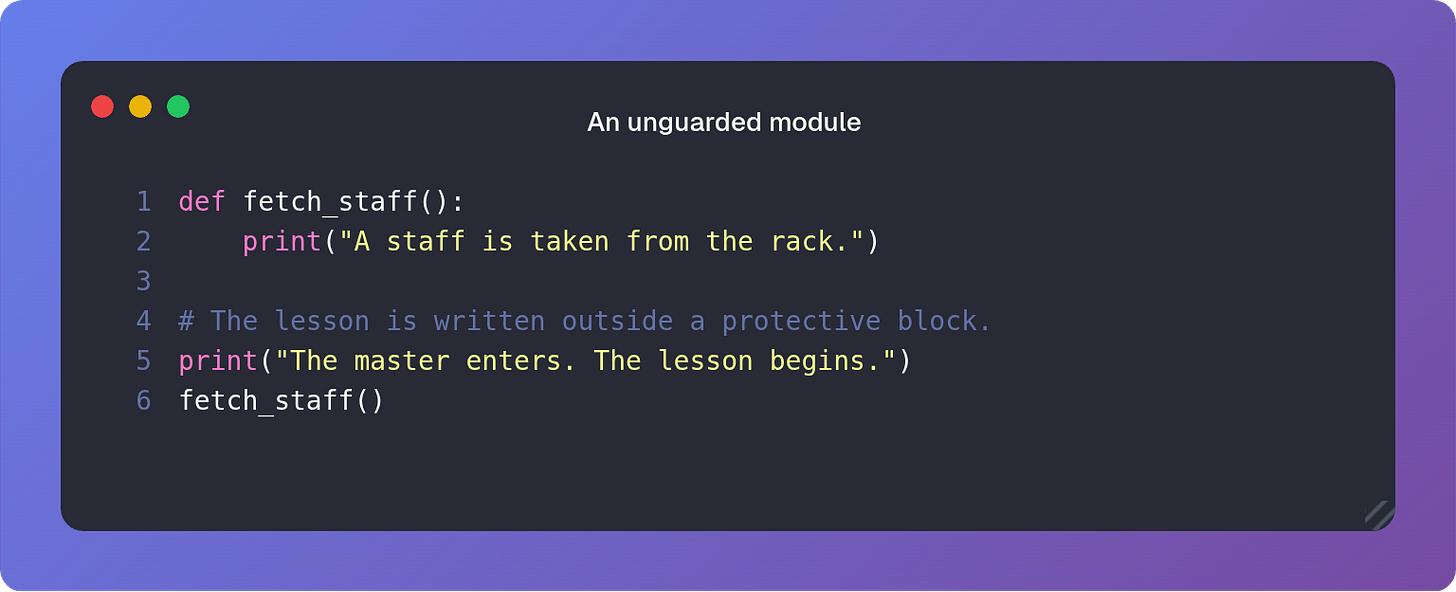

Observe what happens without the protective boundary:

if another file attempts to import this file, the terminal will print:

The master enters. The lesson begins.

A staff is taken from the rack.The lesson begins prematurely. The boundary was not drawn to separate definition from invocation.

The special attribute __name__ is a string that holds the module’s identity.

When the file is executed directly, Python’s master interpreter sets

__name__to the string“__main__”.When the file is imported,

__name__is set to the module’s file name (e.g.,“training_hall”).

The guard acts as a lock:

if __name__ == “__main__”:

conduct_lesson()Now, if imported, __name__ is “training_hall”. The condition is False, and conduct_lesson() is not run.

Part 2: The Breakage of Relative Paths

Sometimes modules use relative imports to refer to its siblings:

When you run python mypackage/temple.py directly, you will be greeted with this error:

ImportError: attempted relative import with no known parent packageWhen run directly, temple.py is not part of a package, so it’s __name__ becomes __main__, not mypackage.temple. Python’s import system expects a module run as main to be at the package root. The relative import from . (the current directory) breaks as the package structure is lost.

The fix is to run the code as a module: python -m mypackage.temple; or switch to a relative import: import mypackage.temple.

Part 3: A Fine Pickle

The pickle module can be used to serialize and deserialize python objects to disk. To do this, it stores object references by their importable path, e.g. mypackage.temple.ClassName. Imagine you had two files - save_code.py which saved an object to disk in the main module, and another - load_code.py which tried to load the pickled object from disk:

This would throw an error:

AttributeError: Can’t get attribute ‘Model’ on <module ‘__main__’>When you define a class or function in __main__, its path is “__main__.ClassName”, which gets saved in the pickled object. When the object is unpickled in load_code.py “__main__.ClassName” doesn’t exist in the module. So data pickled in the __main__ module cannot be re-imported later when unpickling elsewhere. The fix is to ensure that you always pickle in an importable module:

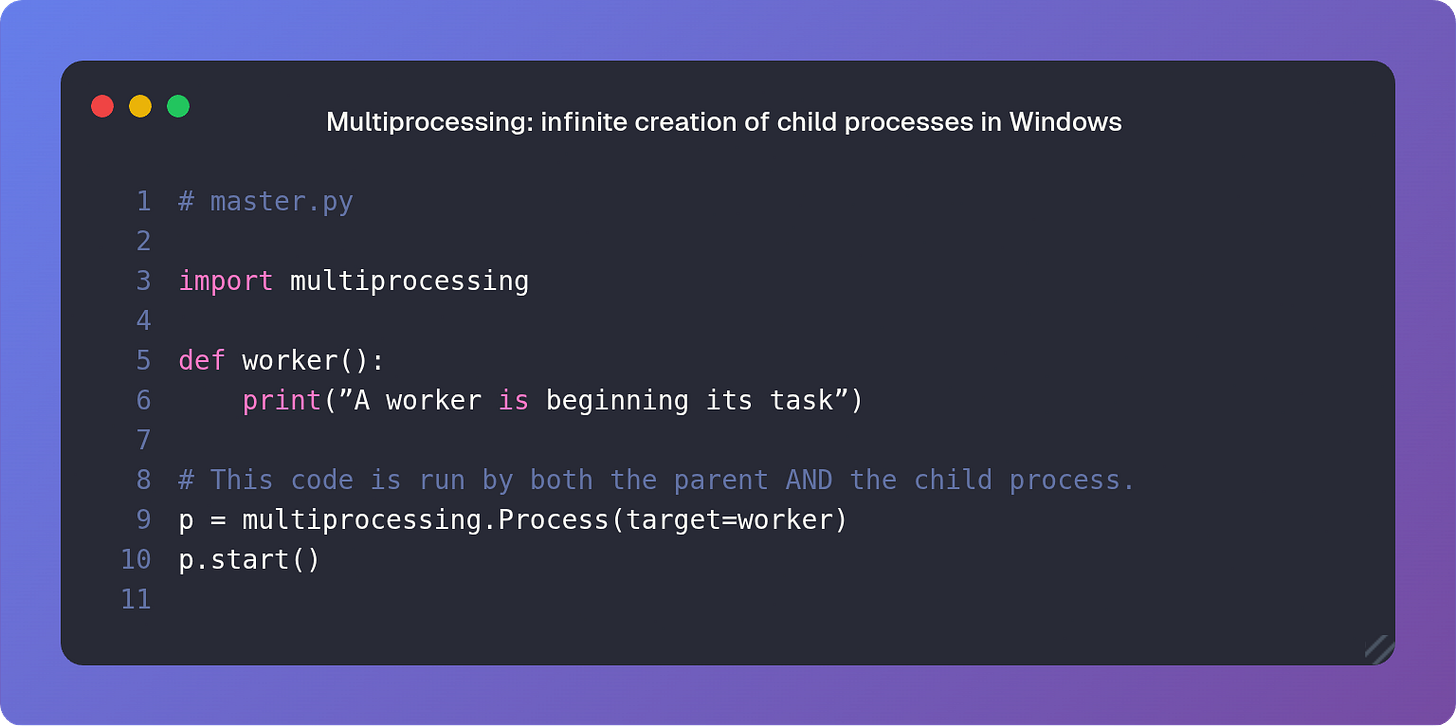

Part 3: The Child Process and the Re-Import

In certain operating systems, especially Windows, Python’s multiprocessing library avoids sharing memory state directly between a parent and its new child process. Instead, it re-imports the entire main module into the new child process to ensure a clean start. Consider the risk:

Without a guard, the child process, upon re-importing master.py, would execute the process creation line again, leading to an infinite creation of child processes.

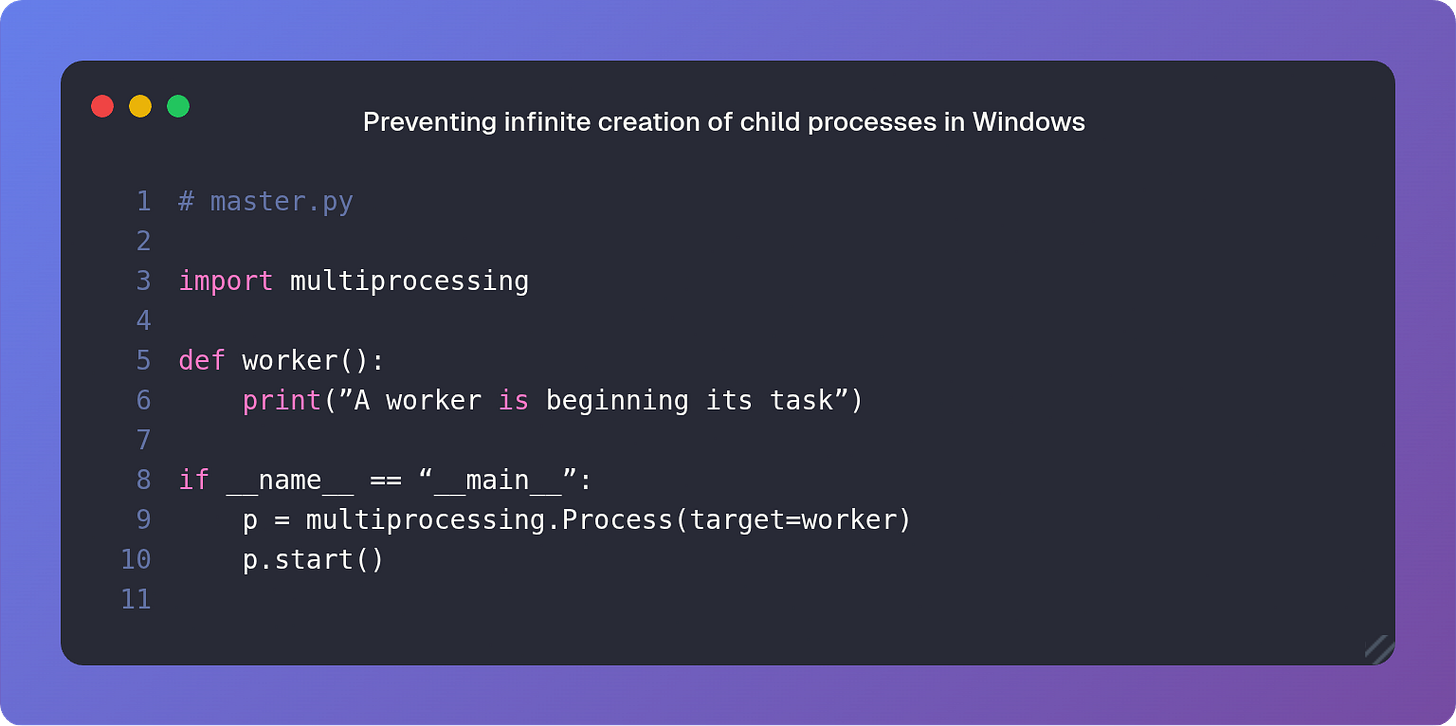

Again, our simple guard prevents this:

The child process, when re-importing the module, sets the module’s name to its file name (e.g., ‘master’), not “__main__”, thus bypassing the process creation code and safely starting its task.

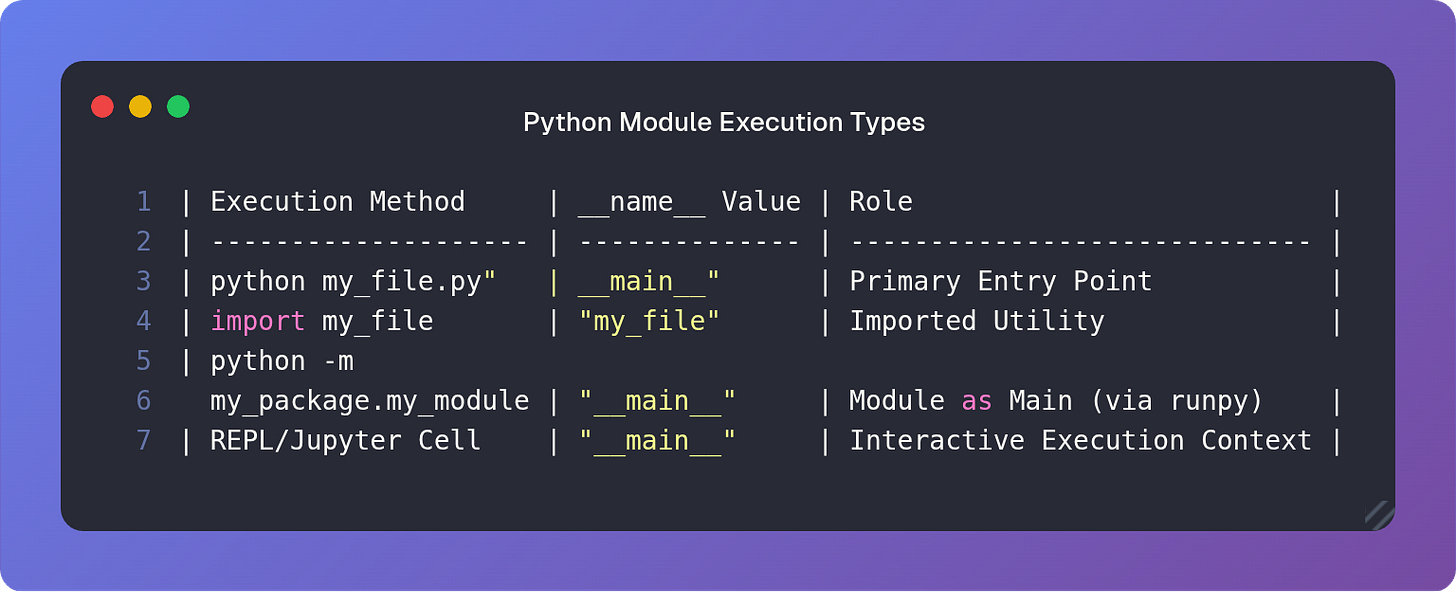

Part 4: Python Execution Types

There are other ways a module may be executed without becoming the true primary executable, each leading to a different __name__ value.

When running a module with

python -m my_package.my_module, therunpy1utility is used. This forces__name__to“__main__”, allowing execution of a module within a package structure.In environments like Jupyter or the basic Python REPL, an executed cell or a pasted block of code is considered the immediate execution context, and its

__name__is also temporarily“__main__”.In test environments (like pytest) or when a file is genuinely imported

__name__will not be“__main__”. Test files are executed as imported modules, not as main scripts, ensuring that their test suites do not inadvertently run the protected code.

Ending The Lesson

The Master’s teaching was simple: the staff stands ready on the rack, until the lesson is initiated by the master. The guard if __name__ == “__main__”: serves as the master’s permission, ensuring that the module’s core logic is run only when needed.

It separates code that is merely defined from code that is executed and answers a fundamental question Python asks of every file it touches: Are you a library I should use, or a program I should run?

“The runpy module is used to locate and run Python modules without importing them first. Its main use is to implement the -m command line switch that allows scripts to be located using the Python module namespace rather than the filesystem” - https://docs.python.org/3/library/runpy.html