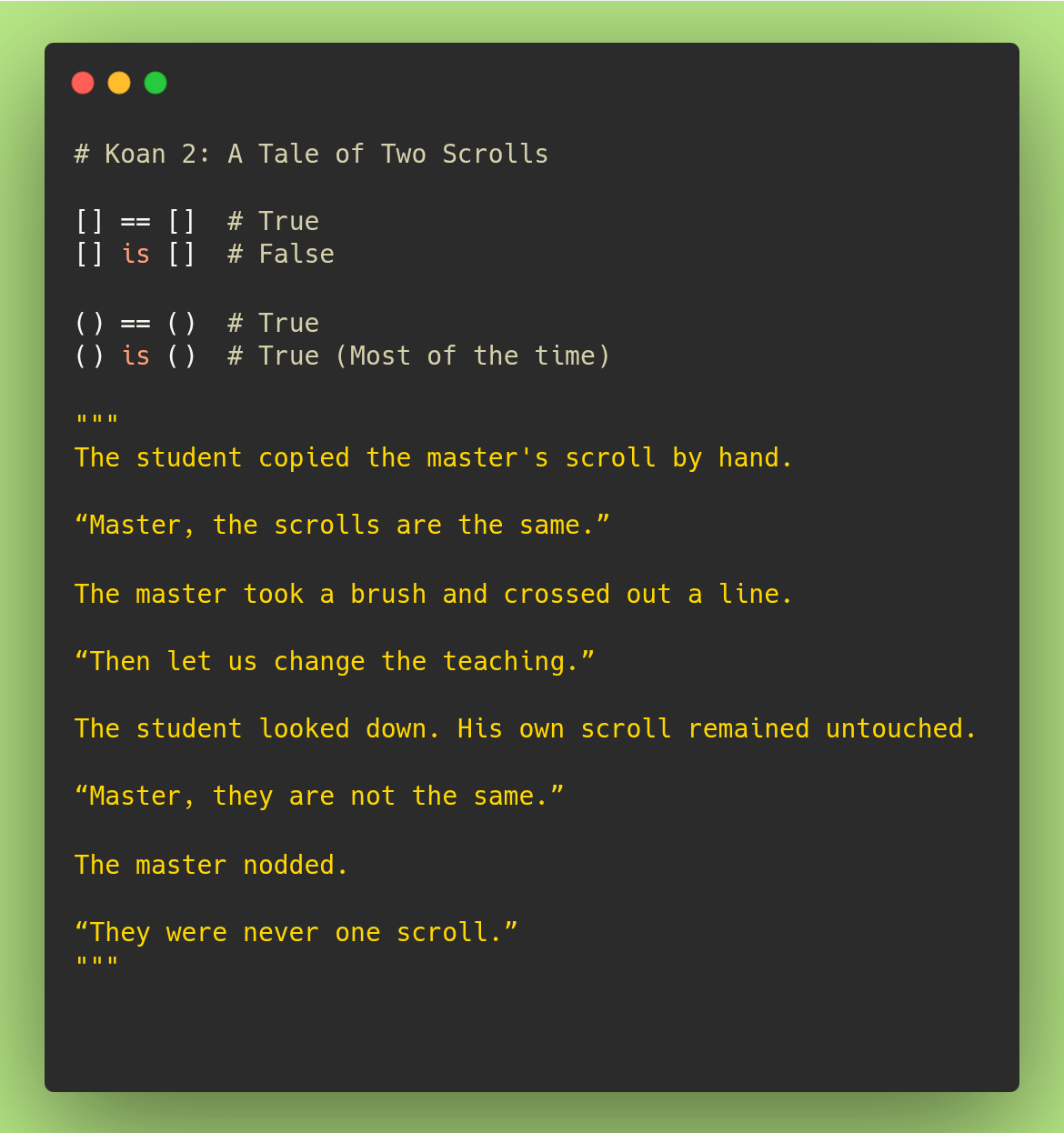

Koan 2: The Tale of Two Scrolls

Understanding the difference between identity and equality, and why it matters more than it seems.

"is" vs. "==": The Subtle Art of Identity and Equality in Python

When learning Python, it's common to encounter subtle distinctions that don’t make much sense at first. One of these is the difference between is and ==. At a glance, they both seem to answer the same question: "Are these things the same?" But in truth, they answer very different questions.

Let us begin at the beginning.

Part 1: The Two Questions

Python allows you to ask:

Do these two values have the same contents?

You use==to ask this question.Do these two values refer to the same object in memory?

You useisto ask this question.

In simple terms:

==asks, "Do they look the same?"isasks, "Are they the same being?"

Let’s look at a few examples:

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = [1, 2, 3]

print(a == b) # True (same contents)

print(a is b) # False (different objects)At first, this might feel strange. If they’re both [1, 2, 3], why wouldn’t they be the same?

Because Python has created two separate lists in memory. They hold the same values, but they are not the same object. Like two scrolls with identical text, one copied from the other. If you edit one, the other remains unchanged.

This is the heart of the difference between equality and identity.

Part 2: Why Use is At All?

Why not always use ==?

The is operator is not about equality of content, it is about identity. There are cases where identity matters deeply. One of them is checking for a sentinel object, such as None.

if user_input is None:

print("No input provided.")Here, you're not asking "Does the input look like None?", but "Is the input literally the None object?"

This distinction ensures clarity and precision when writing code that interacts with unique markers or singleton objects.

Part 3: The Subtle Trap of Immutable Types

Now let’s tread into trickier ground. The behavior of immutable types, such as integers, strings, and tuples.

Consider:

a = 1000

b = 1000

print(a == b) # True

print(a is b) # False (on most systems)But then:

x = 5

y = 5

print(x == y) # True

print(x is y) # TrueWhy the inconsistency?

This is due to an implementation detail of CPython (the most widely used Python interpreter). For performance, CPython caches small integers and some strings. So small values may end up pointing to the same object. But this is not something you should rely on. It's a quirk, not a guarantee.

In other words: the student sees that 1 is 1, and assumes the same for 1000 is 1000. But the truth changes subtly with scale, like mist lifting to reveal two paths instead of one.

Part 4: Containers and Identity

Let’s go a step deeper. What about empty containers?

print([] == []) # True - same contents (both empty)

print([] is []) # False - distinct list objectsPython creates a new list each time you write []. They are separate, though they appear the same. Like the student’s scrolls, word-for-word identical, yet changes to one do not touch the other.

And tuples?

print( () == () ) # True

print( () is () ) # True (usually)Here again, we encounter CPython’s caching. Because () is immutable and common, Python may reuse the same object. But this behavior is not mandated by the Python language specification, it is an implementation detail.

From Python 3.8 onwards, certain comparisons like () is () even raise a SyntaxWarning, gently nudging the student to rethink their assumption.

Best Practices

Use

==when comparing values.

You’re asking, do these two things hold the same meaning or content?Use

iswhen checking for identity, especially for singletons likeNone,True,False, or a sentinel object you define.Avoid using

iswith literals or immutable values, unless you have a specific reason to care about identity, and even then, document that reason.

Final Reflection

The master’s lesson was simple:

Two scrolls may appear the same. But when you change one, the truth of their separation is revealed.

In Python, == and is teach us to look beneath the surface. Equality is about appearance. Identity is about essence. And understanding this difference is not just a technical detail, it is a practice in seeing things as they truly are.

I was just thinking about Liebniz’s Law and how we ought to think about it more often in matters of social identity, it’s incredible how something from philosophical ontology can be mapped to programming too. The idea of *identity* and *properties* of objects and how that relates to equality is at play. Objects in Python are not “the same” if they have different memory blocks, metadata, etc even if the contents are equal. Equal != Indentical. Very cool stuff.