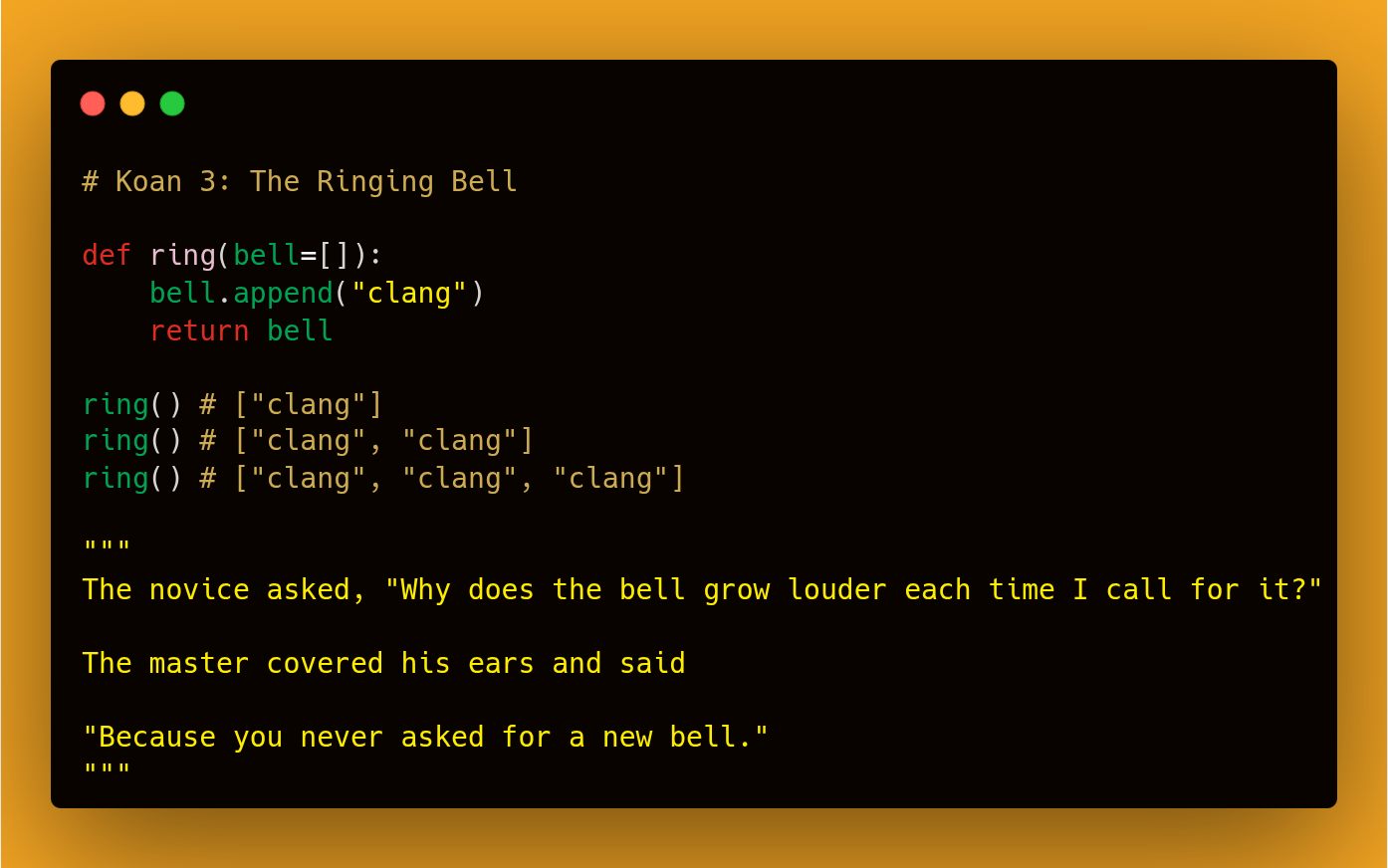

Koan 3: The Ringing Bell

Understanding how Python evaluates default arguments and why mutable defaults can carry unintended memory

Mutable Default Arguments and the Echoes of the Past

In Python, a function is not just a block of code, it is an object, alive with memory. And sometimes, that memory is louder than you expect.

We expect that every time we call ring(), it will create a new list and append "clang". But instead, each call remembers the last. Why?

Part 1: When Are Defaults Evaluated?

In Python, default arguments are evaluated only once — at the time the function is defined, not each time it is called.

So in:

def ring(bell=[]):Python creates a new empty list once and binds it to the bell parameter’s default. All future calls to ring() without a bell argument will use that same list.

Thus:

first = ring()

second = ring()

third = ring()

print(first is second is third) # TrueThey are all the same object.

This behavior often surprises beginners. It feels as if Python is remembering things it should forget. But it is not magic. It is memory: persistent, and shared.

Part 2: Mutable vs Immutable Defaults: A Gentle Contrast

The issue arises only with mutable default values, like lists or dictionaries. What if we used an immutable default, such as a tuple?

Consider:

def ring(bell=()):

bell += ("clang",)

return bellWhat do you expect?

ring() # ('clang',)

ring() # ('clang',)

ring() # ('clang',)Each call gives us a fresh result. There is no accumulation. No echo.

Why?

Because tuples are immutable. The += operator cannot modify the existing tuple. Instead, it creates a new one. In Python, the id() function gives you the memory address of an object. You can use this to test if the objects are the same, but beware of the CPython caching (also known as interning) we learnt about last week. To avoid CPython interning, we need to assign the result to a new object:

import time

def ring(bell=()):

bell += (str(time.time()),)

return bell

sound1 = ring(); print(id(sound1)) # 135080430662176

sound2 = ring(); print(id(sound2)) # 135080430179360

sound3 = ring(); print(id(sound3)) # 135080430181856Want to explore how interning works in more detail?

I’m starting a new companion series where I explore advanced Python techniques in more detail and how they are actually used in open-source projects. It’s called “Python In The Wild”, and you can subscribe here to receive the first post when it comes out:

Each time, Python builds a new object and returns it. The original default remains untouched.

This is why only mutable default arguments pose a problem. It is not the default itself that is dangerous, it is the possibility of mutation.

When an object can change, and you reuse that object across calls, you risk unintended persistence.

Part 3: The Right Way: Use None as a Sentinel

The conventional solution is this:

def ring(bell=None):

if bell is None:

bell = []

bell.append("clang")

return bellNow:

ring() # ['clang']

ring() # ['clang']Each call receives a fresh list.

Why use None?

Because None is immutable and unique. It makes an excellent sentinel, a marker that tells us, “No argument was provided.”

If you use this pattern, your functions will behave predictably. The echoes will fade when they should.

Part 4: When Might You Use Mutable Defaults?

There are rare times when shared mutable state is intended. For example, a function that memoizes its own results:

def factorial(n, cache={0: 1}):

if n not in cache:

cache[n] = n * factorial(n - 1)

return cache[n]Here, the default dictionary acts as a persistent memory. But this is a deliberate choice, not an accident.

If you do this, document it clearly. Most of the time, such patterns are better handled with decorators or external caches.

Shared state is not inherently wrong, but it must be a conscious design, not an accidental side effect.

Best Practices: The Bellmaker’s Notes

Avoid using mutable objects like lists or dicts as default arguments.

They persist across calls and can lead to surprising behavior.Use

Noneas a default when you want a fresh object each time.

Inside the function, create a new object only when needed.Immutable defaults (like

None,0,'', or()) are always safe.

Operations like+=on them return new objects, leaving the default unchanged.If you must use a mutable default, document the behavior clearly.

Treat it as shared state and ensure your design requires it.When debugging, use

id()or logging to confirm whether the same object is reused, but beware of interning which can mislead you.

If your function “remembers” things, ask yourself: “Did I mean to ring the same bell again?”

Closing the Circle

The novice asked, “Why does the bell grow louder each time I call for it?”

The master replied,

“Because you never asked for a new bell.”

In Python, if a default argument is mutable, it will grow, echo, and persist across calls.

To write clean Python is to know which bells echo, and when to ring a fresh one.

This is excellent stuff. I’m not a beginner but this is connecting dots for me to memory in ways I was not thinking about when putting function output together! This series is so good it could be a book.