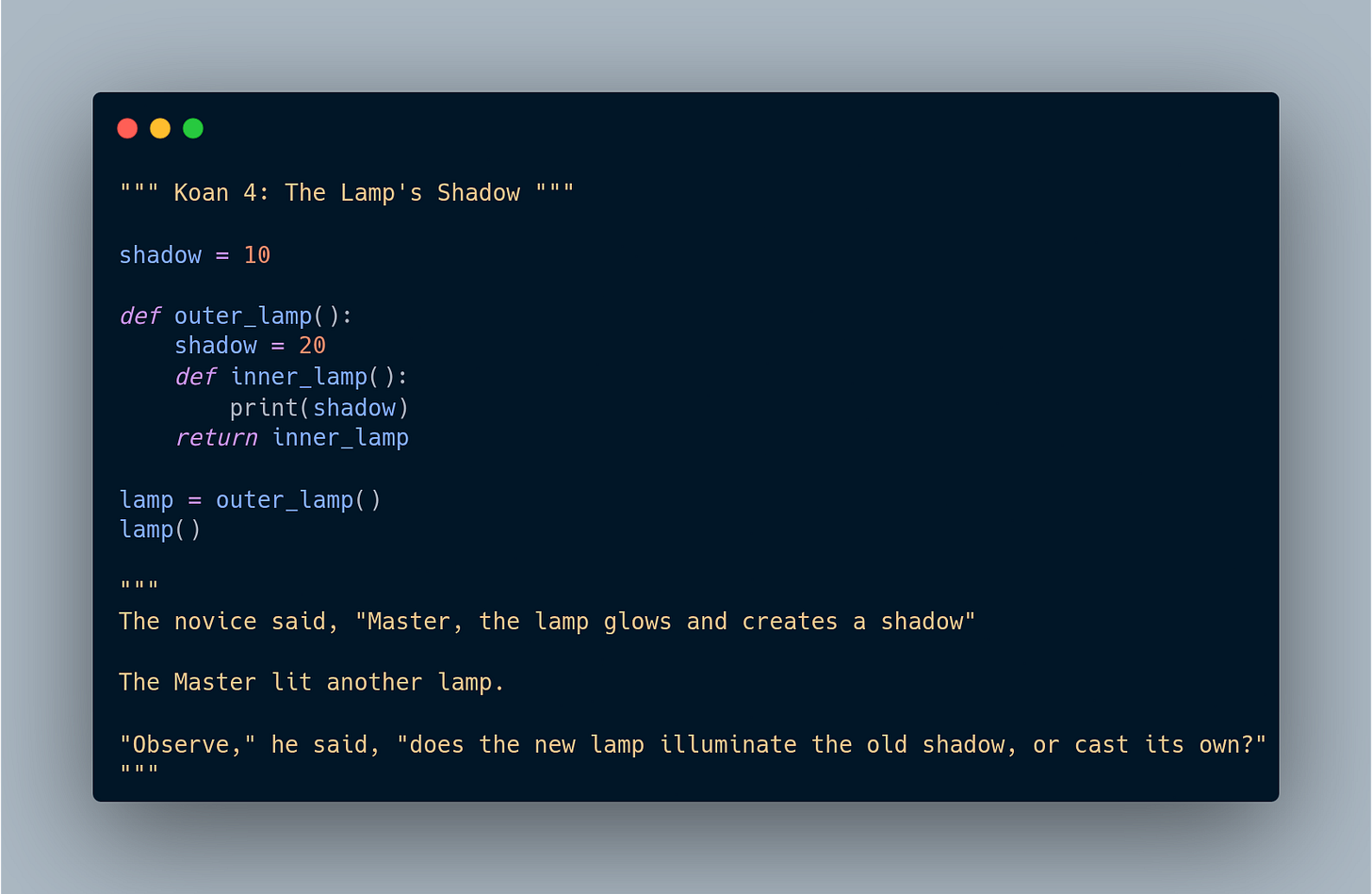

Koan 4: The Lamp's Shadow

Understanding Python’s LEGB rule, closures, and why variables sometimes behave like shadows.

Variable Scope and the Shadows They Cast

In Python, variables are not always where they appear to be.

When a function runs, it carries with it not just its own code, but the shadow of names it has seen, names that belong to outer scopes.

To understand this, we must learn to see how Python resolves names.

Let us begin simply.

Part 1: The Local Glow

The simplest form of scope is the local scope. When you define a variable inside a function, it exists only within that function's execution.

def greet():

message = "Hello, world!"

print(message)

greet()

print(message) # This would cause an error: NameErrorHere, message is born and dies within the greet function. It's like a lamp lit only inside a small room; its light doesn't extend beyond the doorway.

Part 2: The Enclosing Room

Now, let's open another door. Python has a concept called enclosing scope. This applies to nested functions. If a variable isn't found in the immediate local scope, Python looks outwards to any enclosing functions.

Consider this:

def outer_function():

outer_message = "From the outer room."

def inner_function():

print(outer_message)

inner_function()

outer_function()

When inner_function is called, it first looks for outer_message within its own scope. It doesn't find it. So, it looks in the scope of outer_function, where outer_message resides. This works. The inner function can see the variables of its enclosing function, like seeing the light of a lamp in an adjacent room through an open door.

Part 3: The Global Stage

Beyond local and enclosing scopes, there is the global scope. Variables defined at the top level of a script or module are global. They can be accessed from anywhere within that module.

global_message = "From the wide world."

def display_global():

print(global_message)

display_global()Here, display_global can access global_message because it's in the global scope. This is like the sun's light, visible from every room.

Part 4: The Built-in Universe

Finally, there's the built-in scope. This contains all the names that Python pre-defines, such as print, len, str, True, False, and None. These are always available.

The order in which Python searches for names is known as the LEGB rule:

Local (current function)

Enclosing function locals (from inner to outer enclosing functions)

Global (top-level of the module)

Built-in (Python's pre-defined names)

Python stops at the first place it finds the name.

Part 5: When Shadows Deceive - Variable Binding

The true complexity arises when you assign to a variable within a deeper scope. When Python encounters an assignment statement, it assumes you intend to create or modify a variable in the current scope, unless explicitly told otherwise.

Let's revisit our koan's example:

shadow = 10 # Global shadow

def outer_lamp():

shadow = 20 # This 'shadow' is local to outer_lamp()

def inner_lamp():

print(shadow) # This 'shadow' refers to outer_lamp()'s shadow

return inner_lamp

lamp = outer_lamp()

lamp() # Output: 20

Here's the crucial part:

shadow = 10establishes a globalshadow.Inside

outer_lamp(),shadow = 20creates a new, local variable withinouter_lamp's scope. Thisshadowis entirely separate from the globalshadow. It does not modify the globalshadow.Inside

inner_lamp(), whenprint(shadow)is called, Python searches forshadowusing the LEGB rule. It findsshadow = 20in its enclosing scope (outer_lamp), and that's theshadowit uses.

The lamp() call, which executes inner_lamp(), thus prints 20. The global shadow (which remains 10) is untouched, and the shadow in outer_lamp() casts its own shadow, independent of the global lamp.

Part 6: The Illusion of Locality

Now, a subtle twist:

shadow = "global"

def inner():

print(shadow)

shadow = "local"

inner()What happens here?

Python raises an error:

UnboundLocalError: cannot access local variable 'shadow' before assignmentWhy?

Because Python sees the assignment shadow = "local" and assumes that shadow must be local to inner. It does not look outside anymore. So when you try to read shadow before assigning it, Python is confused. There is a local shadow, but it has no value yet.

In Python, any assignment to a variable within a function makes that variable local to that function, unless explicitly declared otherwise.

This leads us to the next teaching.

Part 7: Declaring Intent – global and nonlocal

If we wish to use or modify a variable from an outer scope, we must declare our intent.

Using global:

shadow = 5

def modify():

global shadow

shadow = 10

modify()

print(shadow) # 10Here, global shadow tells Python: “I mean the shadow from the module’s top level.”

When working with nested functions, and using nonlocal:

def outer():

shadow = 5

def inner():

nonlocal shadow

shadow = 10

inner()

print(shadow)

outer() # 10Without nonlocal, the assignment would create a new local shadow inside inner.

With it, Python understands: use the variable from the enclosing function.

Extinguishing The Lamp

The Master's second lamp illuminated the truth: each lamp casts its own shadow. Similarly, in Python, each scope can define its own variables, creating distinct 'lamps' of variables. Without explicit instruction (like nonlocal or global), an assignment always defaults to the current, innermost scope, safeguarding higher-level variables from unintended modification.

Understanding scope is not just about avoiding errors; it's about designing clear, predictable, and maintainable code. It's about knowing where your variables truly reside, and how their light extends, or does not extend, into the surrounding code.