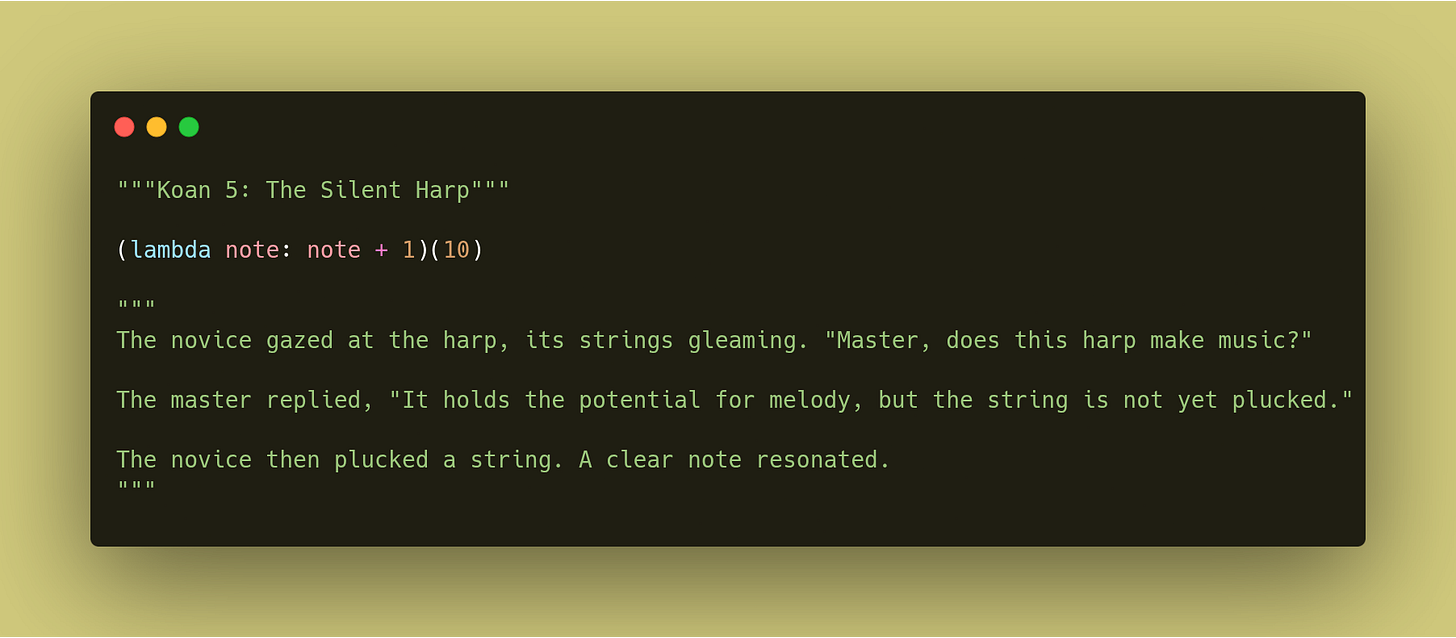

Koan 5: The Silent Harp

Exploring how functions in Python are treated as first-class citizens, and the untapped potential they hold.

Functions as First-Class Citizens in Python

In Python, a function is much like a harp. An object that holds potential, a set of instructions waiting to be invoked and produce a harmonious result. This design choice makes functions "first-class citizens," opening up a world of elegant and powerful programming paradigms.

Let's begin with this fundamental understanding.

Part 1: The Harp’s Existence

What does it mean for a function to be a "first-class citizen"? It means that functions can be:

Assigned to variables.

Passed as arguments to other functions.

Returned as values from other functions.

Stored in data structures (lists, dictionaries, etc.).

This is distinct from languages where functions are merely blocks of code that can be called, but not manipulated like other data.

Consider a simple instruction for making music with our harp:

def play_note(note):

return f"The harp plays the note: {note}"In Python, play_note isn't just a command; it's an object. You can prove this by assigning it to another variable, much like one might refer to the harp by a different name in an orchestra:

my_instrument = play_note

print(my_instrument("C major"))Here, my_instrument now refers to the same function object as play_note. The harp exists, and we have a way to access its potential for sound, even if no note has yet been played.

Part 2: Passing the Harp to the Musician (Higher-Order Functions)

One of the most powerful implications of functions being first-class is the ability to pass them as arguments to other functions. Functions that accept other functions as arguments are known as "higher-order functions." This is akin to handing our harp to a skilled musician, trusting them to play its strings when the moment is right.

A common example is the map() function, which applies a given function to all items in an input list and returns an iterator. Let's imagine we have a sequence of musical ideas, and we want to apply a transformation to each using our harp's capabilities:

def harmonize_note(x):

return f"{x} with harmony"

melody_notes = ["C", "G", "Am", "F"]

harmonized_melody = list(map(harmonize_note, melody_notes))

print(harmonized_melody)Here, harmonize_note is passed as an argument to map. map doesn't know what harmonize_note does, only that it's a callable object it can apply to each element. It simply knows how to take a series of musical ideas and apply the "play and harmonize" instruction to each.

Part 3: The Unnamed Chord (Lambdas)

For simple, one-off musical expressions, Python offers "lambda expressions." These are small, anonymous functions that can be defined in a single line. They are particularly useful when you need a function object for a short period, often as an argument to a higher-order function, like a quick flourish instead of a formal composition.

Our koan's core, lambda x: x + 1, is an example of an anonymous function. It exists, it holds potential, but it doesn't have a formal name.

# Using a lambda with map to transpose notes:

base_frequencies = [440, 494, 523] # A4, B4, C5 frequencies

transposed_frequencies = list(map(lambda freq: freq + 50, base_frequencies))

print(transposed_frequencies)Lambdas are succinct and often improve readability for simple operations, avoiding the need to define a full def function for a trivial task. They are like a quickly improvised chord on the harp.

Part 4: Plucking the String Immediately (Immediate Invocation)

Just as we can assign a lambda to a variable and then play it, we can also play it immediately after it's defined.

Consider our simple lambda from the koan:

lambda x: x + 1This defines a function object. It is the silent harp string. To make it produce a result, we need to "pluck" it by providing an argument. We typically do this by assigning it to a variable first, then calling that variable:

increment_frequency = lambda x: x + 1

result = increment_frequency(10)

print(result)However, because the lambda expression itself evaluates to a function object, you can immediately apply arguments to it, just like you would with any other function reference.

The koan's code demonstrates this:

(lambda x: x + 1)(10)Here, (lambda x: x + 1) creates the anonymous function object (the harp string), and (10) immediately calls that function with the argument 10 (plucks the string). The parentheses around the lambda expression are crucial here to ensure the lambda is fully defined before the invocation operator () attempts to call it. Without them, Python would expect a function name to call.

This pattern, sometimes seen as an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE), is less common in everyday Python than in JavaScript, but it is perfectly valid and can be seen in specialized contexts, often for creating self-contained scopes or for quick, single-use computations without cluttering the namespace.

Closing the Circle

The silent harp holds all its potential for music within. Only when a string is plucked does its melody emerge. And sometimes, the note is played the very moment the string is tied.

In Python, functions are not just commands; they are entities with identity, capable of being manipulated, stored, and passed around like any other piece of data.